Villanova's second national title in school history was the culmination of coach Jay Wright's 15 years of painstakingly building the unheralded program, through ups and downs, heartbreak and triumph. In Long Shots: Jay Wright, Villanova, and College Basketball's Most Unlikely Champion, Dana O'Neil not only explores behind-the-scenes of the historic 2015-16 NCAA championship season but also the improbable path that the Nova program took to college basketball immortality. In overcoming a disappointing NCAA Tournament track record, the breakup of the Big East conference as we knew it, and Nova's underdog status among traditional college hoops powerhouses, Jay Wright and his team provided the blueprint for how a "have-not" can prevail over the blue bloods the right way – the Villanova Basketball Way.

The Villanova players gathered round like they always do, a tight circle surrounding Jay Wright. Ryan Arcidiacono sat directly across from his coach; Kris Jenkins was at Wright's left elbow. Wright scribbled a few things on his whiteboard and everyone listened intently.

Seconds earlier North Carolina's Marcus Paige had connected on a circus three-point shot to tie the score at 74–74. Only 4.7 seconds remained for Villanova to win the national championship or settle for overtime. NRG Stadium practically buzzed with energy. At their courtside seats, reporters frantically rewrote their deadline stories. In the stands, even all the way up to the nether reaches of the dome, fans stood on their feet, too amazed at what just happened, too nervous to watch the end.

Yet that Villanova huddle, the one place that should have been frantic and chaotic, was an oasis of calm. No one spoke over each other or screamed. Really no one, aside from Wright, said a word. Instead, every player, assistant coach, and even manager stared intently as the coach began to speak.

How did the Wildcats, prepping for the biggest possession of the college basketball season, stay so relaxed?

Simple.

Jay Wright taught them.

When he first arrived on the Villanova campus in 2001, Wright introduced his players to Attitude Club. Admission is neither free nor open to everyone. Players earn their way into the exclusive group by leaving skid marks on the floor diving for a loose ball, bruising their backside taking a charge, stretching for an extra inch in their vertical leap to tap back a rebound, or any of a myriad of hustle plays that don't show up in a box score. Every time the Wildcats compete, a staff member charts attitude points and a winner is declared after each practice, each game, and at the end of the season. Leading in attitude points is more coveted than leading the team in scoring.

To Wright -- and now by extension to his players -- attitude, not points, wins games. How a player prepares himself and supports his teammates, how he carries himself in victory, in defeat, and especially in the most difficult times, is the difference between winning and losing.

And so when the Wildcats circled up for the last huddle of the 2015–16 season, even with just 4.7 seconds left to cover 94 feet of open floor, they were ready.

"It was like, 'Okay, this is what we've been working toward.' Not the national championship itself, but what we call preparing for the most difficult situation," said associate head coach Baker Dunleavy.

"Everyone's mentality was, 'Okay, I'm not going to be the one that loses his cool. I know what my teammates are thinking, what my coaches are thinking, so I'm going to fall in line.' As crazy as it sounds, we almost practice for it."

The all-time Attitude Club champion?

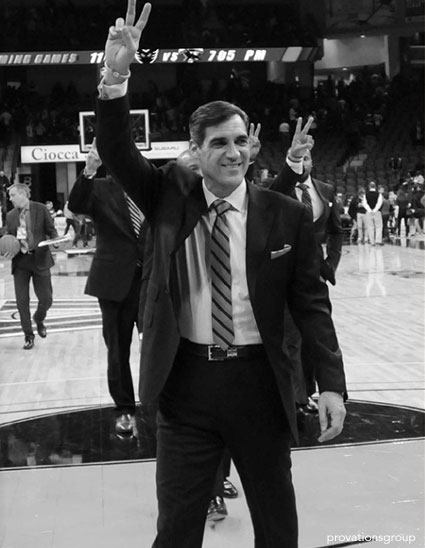

That would be Jay Wright. People love to talk about Wright's looks and menswear finery -- his suits even have their own Twitter handle, @JayWrightsSuit. While other coaches wrestle with neckties that appear to be choking them, or give in to shirttails that refuse to stay tucked, Wright is permanently pressed. President Barack Obama even referred to Wright as the "George Clooney of coaches." From his pocket square tucked neatly in his suit pocket to his hair coiffed to perfection, he is the personification of the old Gillette advertisement -- "Never let 'em see you sweat."

The motto fits more than his appearance. It suits his demeanor as well. Wright is a fierce competitor. Players, friends, and fellow coaches love nothing more than to debunk the theory that Wright is as easygoing as his pleasant personality might suggest. But as he's grown as a coach, he's developed an almost inverse reaction to stress -- the tighter and tougher the situation, the more relaxed he is.

So when Wright sat down to illustrate the Wildcats' final play -- a play everyone already knew -- what he said wasn't important. It was how he delivered the message.

"Calm, cool, and collected, that's him to a tee," said Speedy Claxton, who played for Wright at Hofstra. "His teams feed off of that. You play the way he is."

Mike Mikulski, Wright's best friend since childhood, remembers a similar huddle some 40 years ago.

During a timeout, Mike Holland, the Council Rock High School boys basketball coach, gathered his players around in the midst of a tight game and drew up a play. The boys listened intently, understood what was being asked of them, and then headed on to the court. Except before the referee whistled to begin play, one of the boys called his teammates together. There, without a clipboard -- and more, without his coach's knowledge or consent -- Jay Wright changed the play.

"And here's the thing," Mikulski said. "Everyone fell in line. We changed the play."

Understandably furious afterward, Holland screeched at Wright to never upstage him like that again, reminding him that the play he designed would have worked. Wright smirked.

"Mine did, too," he said.

"I said he was competitive. I never said he was easy," Mikulski laughed, recalling the story.

There are more signs like that, ones that with hindsight seem to predestine Jay Wright to becoming a head coach. He was a hardworking and overachieving first-born child; the son of a fundamentals-first father and a gregarious mother; academically and athletically gifted; voted best dressed and best looking, yet never stand-offish; a starter one year and a bench player the next, all traits that serve a coach well.

But Jay Wright did not grow up with a grand plan. He loved Villanova basketball as a kid, but never once told his buddies he wished he could coach there. He starred at basketball, and yet didn't envision spending his life on a court.

He was merely driven and confident, even if he didn't always know exactly where he was headed.

"Jay just did stuff and it never dawned on him that it might fail," Mikulski said.

Even today, Wright has a casualness about his success. Days after winning the national championship, he sat in his office trying to understand what had happened. He couldn't comprehend it -- not just in the sense that he was amazed by the exciting finish of the game itself. He couldn't grasp what it all meant -- for Villanova, for basketball, and especially for him.

"I just feel like we won a big game," he said. "You know, you win a big game, people in the media call you for a few days. That's what this feels like. When someone says that we won a national championship or we're national champions, it doesn't seem real."

Those who know him well say he's always been like that, consumed with the goal of winning but not drunk on the aftermath of glory. That's unusual, especially in the profession that Wright has chosen.

College basketball, unlike the NBA, is ruled by its coaches. The athletes move on after a quick stopover on campus. Coaches stick around. If they are good, they become the face of a program. If they are great, they become icons. Success typically equals bigger salaries, more demands, and less reality.

Wright isn't a fan of that exchange.

When he first arrived at Villanova, he stood on tabletops in the cafeteria, desperate to drum up interest in the program. Fifteen years later, he still loves to ride around campus in a golf cart, chatting up students, even stopping to purchase a T-shirt from the women's soccer players selling them at a table.

Since the national championship game, he has talked hoops with the president of the United States, but says he most looks forward to a few days off at his house on the Jersey Shore.

"My wife, when she first met him was like, 'Oh God, right. Look at him,'" said Wright's former assistant Joe Jones. "After a month of being around him, we were going home after an event and she looked at me and says, 'You're 100 percent right. He's as nice and as good as you said.' I was stunned. I said, 'You questioned that?' She said, 'Totally.'"

It's a common mistake. If Wright has battled anything throughout his career it is the misconception that, because he looks a certain way, he must be a certain way. "Tailored suits, million-dollar smile, and the personality, but what people fail to see is the depth," said Father Rob Hagan, an associate athletic director who goes by Father Rob and a regular on Villanova's bench.

In some people that has understandably cultivated envy. Even Wright's younger brother, Derek, said he sat him down for a heart-to-heart a few years ago explaining that, as a basketball coach himself, sometimes it was hard to compete with the image of Jay Wright.

"He was like, 'Wow, really?'" said Derek, the head coach at Council Rock South High School, and younger than Wright by 13 years. "He never thought of it that way. But I explained how it was making me feel inadequate and he totally understood."

In others, Wright's appearance has fostered doubts. Early in his career plenty of people thought he was nothing but an empty head in a pretty suit, that he'd be overmatched when he went toe-to-toe with the real leaders of the game.

The truth? As of the end of the 2015–16 season, against Syracuse head coach Jim Boehiem, Wright is 12–9. Against Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski, he's 1–0. Against Louisville's Rick Pitino, he's 6–5. Those coaches are all in the Hall of Fame. As for Wright?

"He doesn't care," Jones said. "He's always been above all of that."

So where does such confidence, such an ease in oneself, come from?

"You know that saying, 'raised right'?" Mikulski said. "Well, he was raised right."

Quintessential baby boomers who grew up in northeast Philadelphia but raised their family in the suburbs, Jerry and Judy Wright taught their kids to work hard but dream big. Jerry -- Big Jer, to the neighborhood kids -- worked as a power tools salesman and spent his evenings coaching the boys in Little League. He believed in teaching fundamentals but also delivered one common refrain to every group he coached -- any team is only as good as its weakest player. Consequently, Big Jer made sure there was no such thing as a weak player, developing every kid to his fullest potential.

The strategy worked. As 10-year-olds, the Larks finished 18–3, losing the championship after poor Artie Gable, who Wright recalls as a great kid and a terrific lefty pitcher, failed to tag up at second base, negating a would-be sacrifice fly on the next play. A year later, they avenged Gable's mistake, winning the league championship. Big Jer was friendly, if a bit more stoic with his emotions.

Judy, meantime, was the yin to her husband's yang. A homemaker, she made a home that was open to everyone. Gregarious, tall, pretty, and always impeccably dressed, Judy has never met a stranger -- sometimes to her kid's embarrassment.

"I didn't appreciate it then, but now I see how his parents were very progressive," Mikulski said. "They were really good at fostering confidence. They weren't restrictive. My mom was the typical Italian mother. She was a lunatic, militant. His parents, they certainly disciplined their kids, but they gave them a lot of rope."

"The Golden Child," his siblings teasingly call the always overachieving Wright. If the neighborhood kids played basketball in the driveway until 10:00 pm, Wright would stay out until 11:30, working on his shot. When it was time to choose up sides for a game, he was always one of -- if not the -- first chosen. Academically, he was part of the school's gifted program. Athletically, he was good enough to be a quarterback on the football team, and a shortstop on the baseball team had he not elected to concentrate on basketball.

Living up to such high standards can, however, exact a toll. Wright never said as much, but his brother sensed it. Wright can be consumed by doing things well, relentlessly pursuing perfection to the exclusion of everything else.

"Maybe it's the Protestant in us, or the northwestern European heritage, but it's almost like you can be so concerned about doing the right thing and what you should do, you don't even necessarily enjoy the moments as they happen," Derek said. "Showing your vulnerability, that's a limit for all of us sometimes."

Wright compensated by never being vulnerable, plastering a smile on his face and soldiering forward.

Though he didn't intend to be a coach early on, Wright had plenty of people to model himself after. There was Big Jer, of course, but Wright also grew up in the heyday of Philadelphia's Big 5 basketball tradition. Harry Litwack, Jack Kraft, and Chuck Daly were among the great coaches to prowl the sidelines back when Saint Joseph's, Temple, Penn, La Salle, and Villanova played a full round-robin schedule.

The basketball itself was even better. Every City Series game was staged at the historic Palestra, often as double-headers. In 1979, the same year that Wright would graduate from Council Rock High School, the University of Pennsylvania would reach the Final Four. But Villanova was Wright's favorite team.

"I know people today say that's all BS," Mikulski said. "It's not BS. That's who he rooted for."

When he wasn't watching games, Wright was playing. In high school, he'd jump in his first car, a Capri, and drive to the Sonny Hill League, the renowned basketball summer league in North Philadelphia. Even there, a suburban small fish in the inner-city big pond, he made friends. He'd come home and persuade his buddies to head outside of their comfy suburban confines for pickup games. Naturally, they'd go.

A talented, long-armed guard, Wright earned some college attention, opting to attend Bucknell University, a small school with rigorous academics about three hours west of Philadelphia.

Wright and his buddies back home figured he'd continue on as always, sliding right in with the team's roster. But being the star at Council Rock isn't quite the same as being a college athlete. Even at Bucknell, a school a few rungs removed from the sport's upper echelon, Wright soon learned that lesson. In letters to Mikulski, who attended La Salle, Wright told his friend about the talented players on the Bison roster, guys such as Albert Leslie, who would go on to become a second-round NBA pick. Wright admitted to being a little overwhelmed and for the first time feeling a little less than confident.

That, however, didn't stop him from bringing the same intensity to the college courts as he did to his own driveway. Pat Flannery was a senior when Wright arrived on campus. He immediately took a liking to the new kid and Wright long has called Flannery one of his mentors. The first time Flannery saw Wright play -- in a pickup game against his future teammates -- he knew Bucknell had found a competitor.

"He tried to challenge the score and calls with a group of pretty good upperclassmen," Flannery said.

Wright earned a starting spot as a junior, but as the roster continued to improve, his playing time diminished. By his senior year he was coming off the bench, a humbling experience for a kid who'd always been picked first, and one he understandably didn't enjoy. Years later, as he grew into a coach, Wright often recalled his own college experience. He learned not only the value of a good bench, but also the importance of making certain that players outside the starting lineup felt as vital as the ones leading the team in scoring.

It was like he was living his father's old motto -- a team is only as good as its weakest link.

-- Excerpted by permission from Long Shots: Jay Wright, Villanova, and College Basketball's Most Unlikely Champion by Dana O'Neil. Copyright (c) 2017. Published by Triumph Books. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Follow Dana O'Neil on Twitter @ESPNDanaOneil.